Sentimental Value is a dramedy about an acclaimed director who travels back to his childhood home to shoot his most personal film yet, but his return brings up complicated feelings for his two estranged daughters. It is co-written and directed by Joachim Trier. This is his second collaboration with actor Renate Reinsve, whose breakout role was in Trier’s 2021 film, The Worst Person in the World. The film premiered at this year’s Cannes Film Festival where it competed for the Palme d’Or and won the sought after second prize, The Grand Prix.

After the death of their mother, sisters Nora and Agnes must face their distant father, Gustav, as they sort through her belongings in the family estate. Nora is an ambitious stage actress who has prioritized her creative goals over her personal relationships, while Agnes has a stable job, husband, and son. Gustav was a once famed director, but has not made a movie in 15 years. Fearing the end of his life, Gustav is eager to define his legacy one last time. He writes a personal and autobiographical film about his mother who took her own life in the home where he raised his daughters.

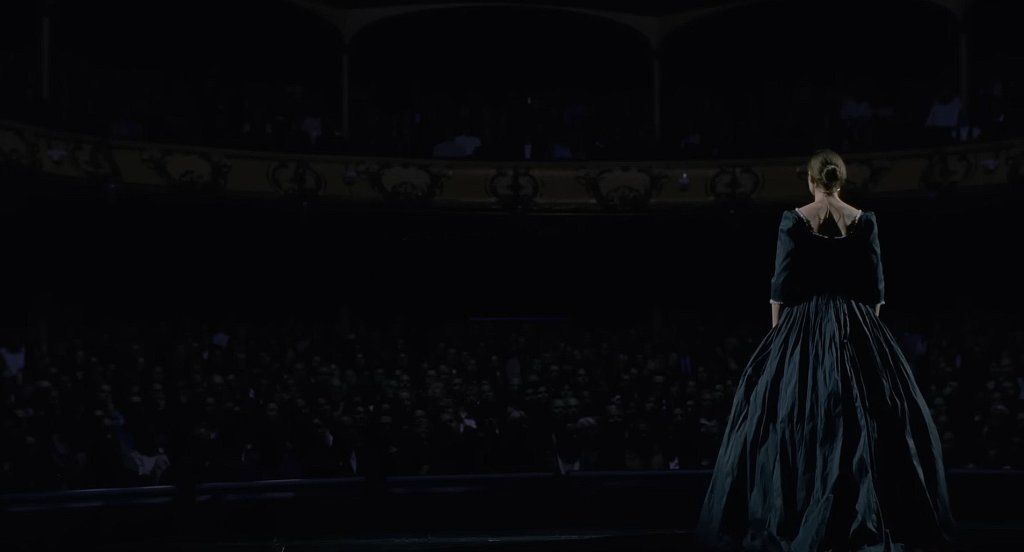

Gustav wrote the lead role with Nora in mind and asks her to accept the part. Nora refuses, completely uninterested in working with the man who chose his career over her. Later at his retrospective screening, Gustav meets Hollywood actress Rachel Kemp and casts her as his mother. Rachel is quick to accept, looking for a character with more substance, but she struggles with the material. Gustav is desperate to use this moment as an opportunity to bookend his career with a final statement and mend the broken bond with his children.

A breathtaking meditation on memory and the subjectivity of the past. How our experience is filtered through these perceptions, shaping the narratives we tell about ourselves. Who we are as people is not defined solely by events in time, but by how those moments shape our sense of self. Nora and Agnes grew up in the same house, with the same parents, with the same trauma, and yet as adults, they differ vastly. Agnes did not let her parent’s divorce determine whether or not she’d have a family of her own.

That’s not to say she wasn’t impacted by it, but rather her approach comes from wanting to “do it right,” as opposed to Nora who would rather not do it at all. Agnes wants her son to have a relationship with his grandfather who was largely absent from her childhood. However, she is hesitant to let him be in Gustav’s movie. She knows what it’s like to be the object of her father’s adoration and the devastation that follows when he moves on to the next, exciting venture.

Despite having her onscreen debut as a child in one of Gustav’s films, Agnes does not pursue acting seriously. Seeing her father abandon his family in pursuit of his craft was more than enough to keep her from an acting career. It’s the very same reason that Nora has for choosing acting over a family because she experienced firsthand what it’s like when a parent doesn’t choose. Nora is an intense and emotional person who doesn’t as easily forgive her father’s shortcomings as her sister does. She wields her resentment against him like a weapon, careful to keep everyone at a safe distance. But deep down, she’s hurting. A hurt that she comes by honestly as it has been passed down to her through generations.

Gustav seeks to understand himself within his family, but lacks the interpersonal skills to do so through normal relationships. In order to process any of this, he must work through these feelings with his art. So he develops a film about his mother who died by suicide when he was just a boy. Over sixty years later, Gustav is still trying to make sense of this senseless act and his feelings of abandonment, recounting the final moments he saw his mother alive. He sees his mother’s misery within Nora which inspires him to write the film with her in mind.

Nora has gone through her fair share of mental health struggles, but has never opened up to her father about them. So Agnes and Nora are shocked when they finally read the script and the parallels between the character and Nora are striking. Could this simply be a coincidence or generational trauma rippling through time? Possibly, but it is also likely that even if Gustav lacked the emotional maturity to reach out to Nora in her time of crisis, he still cared deeply about her pain.

Is creating art a healthy way to process pain? It’s hard to say. Mining the finer details of our lives can feel like an exercise in detachment. A laundry list of trauma, heartbreak, and goodbyes which can be retrofitted in imagined scenarios to give the appearance of authenticity. One moment in Sentimental Value sticks out, occurring after a difficult conversation between Nora and Gustav. When he inevitably disappoints her yet again, Nora bursts into tears and throws herself onto her bedroom floor, only for the shot to go wide revealing that Nora is actually in an audition. None of it is real. Not her tears or her words, she’s not even in a real room.

Yet the emotions are true, used as fuel and dispensed through her acting. The same can be said for Gustav who finds it near impossible to have an honest conversation with his daughters. Whenever challenged on his failures as a father, he pivots to a conversation about his work. This is a deflection of course, but it does not come from a place of cruelty. It’s just the only way Gustav is able to be honest with himself and others, when life is simulated and he is in control of the narrative. Observing from behind a camera in the safety of a constructed environment. This dedication to his craft and desire to understand his own life is ultimately used as a force for good to bring his family together in the wake of tragedy, but his endless ambition is the very thing that broke his family apart in the first place.

A melancholic stunner. My heart was in my throat the entire time.

Leave a comment