No Other Choice is a satirical thriller about a recently unemployed father who takes drastic measures to support his family and maintain their comfortable, upper middle class way of life. South Korean filmmaker Park Chan-wook directed and co-wrote the film, adapted from Donald E. Westlake’s 1997 novel The Ax. The novel was previously adapted into the 2005 French language film, The Axe. Park had plans to adapt the novel as far back as 2009, stating that it was a lifetime goal to bring this story to life through his vision. In 2024, filming for the project had finally begun.

The film premiered at the 82nd Venice International Film Festival where it competed for the Golden Lion. Neon acquired the international distribution rights to the film and South Korea has submitted it as their official entry into the Best International Feature category at the Academy Awards.

Man-su is a proud and lauded long time employee of papermaking company Solar Paper. He lives comfortably in his renovated childhood home with his housewife Mi-ri, his stepson Si-one, and their younger daughter Ri-one, a cello prodigy. When an American company announces their acquisition of Solar Paper, Man-su is surprised to be one of the terminated employees. He promises his family that he will return to work in the paper business in less than three months.

Over a year passes and Man-su is stuck doing low paid retail work while still struggling to get an interview. The family must downsize on the creature comforts that they have taken for granted, including relinquishing the dogs to Mi-ri’s parents in the meantime. Mi-ri accepts part time work as a dental assistant, but it’s not enough to make ends meet. They struggle to pay the mortgage and consider selling the family home to Man-su’s horror.

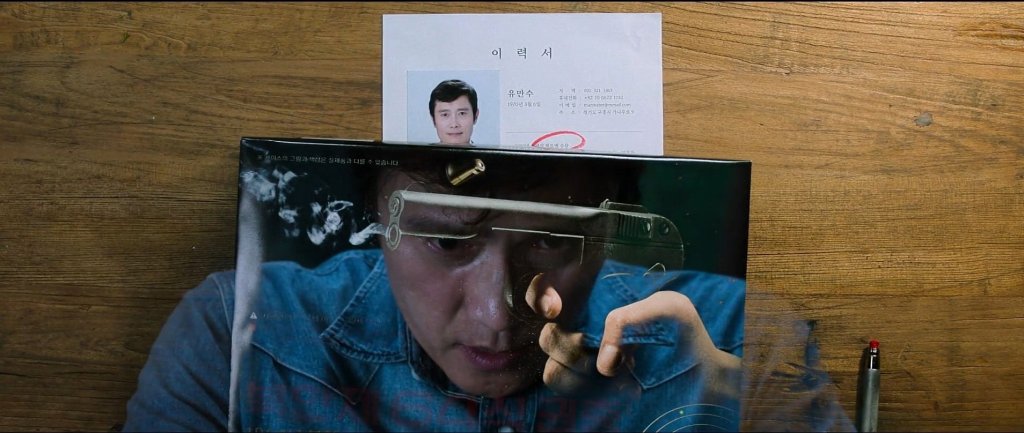

When Man-su finally lands an interview with Moon Paper, he is humiliated by manager Seon-chul. Enraged by the manager’s behavior and so desperately wanting his job, Man-su devises a fake paper company to receive his competitors’ job applications. When it becomes clear that the other applicants are more qualified than he is, Man-su pursues desperate measures to eliminate the competition.

Times are dire. Or at least that is the overwhelming sentiment from everyone you talk to, regardless of their walk in life. In response to these increasingly isolating circumstances, filmmakers have attempted to understand the horrors of modernity and what it takes to survive these conditions. Will we keep our heads down and power through each setback? Will we try to lift up and support each other instead? Or will we simply look for someone to blame? Preferably someone we don’t know. Even better if that person aligns with our biases or prejudice.

What this looks like in 2025’s media landscape is a growing subgenre of “eat the rich” movies which correctly identify wealth inequality as the issue of our time, but incorrectly reduce all societal ills to a small collection of caricatures who have no real political ideology beyond greed.

I empathize with this depiction because it is incredibly easy to buy into the cartoon villainy with the kinds of people currently in charge of all aspects of public and private life. But I think this lets them, ourselves, and everyone who supports these power structures, off the hook too easily. It has become acceptable to throw our hands up, say “there’s no ethical consumption under capitalism,” and continue on as normal, completely uncritical of our place in this ecosystem. As if acknowledgement is the first and only step.

Which is where No Other Choice gets its name. It is the embodiment of this dereliction of responsibility. Accepting an omnipotent inevitability that defies personal agency. Sorry pal, these gears won’t grease themselves and progress stops for no one so either get in or get out of the way. There is no choice. But is this true? Or is it something we tell ourselves to make peace with our portion of the horrors?

It doesn’t take much to push Man-su to the breaking point. After decades of work in the only industry he’s ever known, he’s unceremoniously fired by an American company looking to tighten up the books. Man-su’s nightmare began the second he was reduced to a number on a spreadsheet and determined to be disposable. But his alienation started much sooner. Throughout No Other Choice, characters conflate their profession with who they are. Their identity is defined primarily through this. What they contribute to capital and what they provide for their families is the only meaningful part of these men’s lives. Without it, they succumb to depression and alcoholism, listless ghosts of their former selves.

At the suggestion that these men seek different sectors, they are instinctively defensive. Would you ask a dog not to bark? No, then don’t ask me to do anything but paper. It’s partially a joke, but Man-su is awarded Pulp Man of 2014 (or something like that) and defends his credentials with it on multiple occasions. This is obviously a point of pride for Man-su, especially when the proof of his success is his happy, comfortable family living in the home of his dreams. The danger of buying into a system as volatile and unconcerned as this, is that everything gained can just as easily be taken away.

If the story ended with Man-su retiring to retail work and Mi-ri picking up the slack with a part time job, you could leave the theater feeling sorry for the man. But Man-su does not stop there. He’s determined to weasel his way back into middle management by any means necessary.

This leads to Man-su hatching a plan to kill the other, more qualified, job applicants to increase his chances of getting the offer. An insane idea, made only more so by the knowledge that Man-su’s family is not so desperate that they need to resort to violence. When he makes this decision, the family’s idea of cutting back means less meat in the stew and canceling their Netflix subscription. And you thought the faceless CEOs were anti-social freaks?

In fairness to Man-su, it’s not easy for him. He bumbles around, hardly capable of being sneaky, drenched in sweat, and with hands so shaky, it’s obvious he’s never fired a gun before. Imagining their deaths was so much simpler when they were headshots and resumes on a desk. But as living, breathing people, begging for their lives? Man-su has to keep his head down and push through in order to get this job done. Yet, the guilt never fully catches up with him because in his mind, he remains steadfast in his belief that he had no other choice.

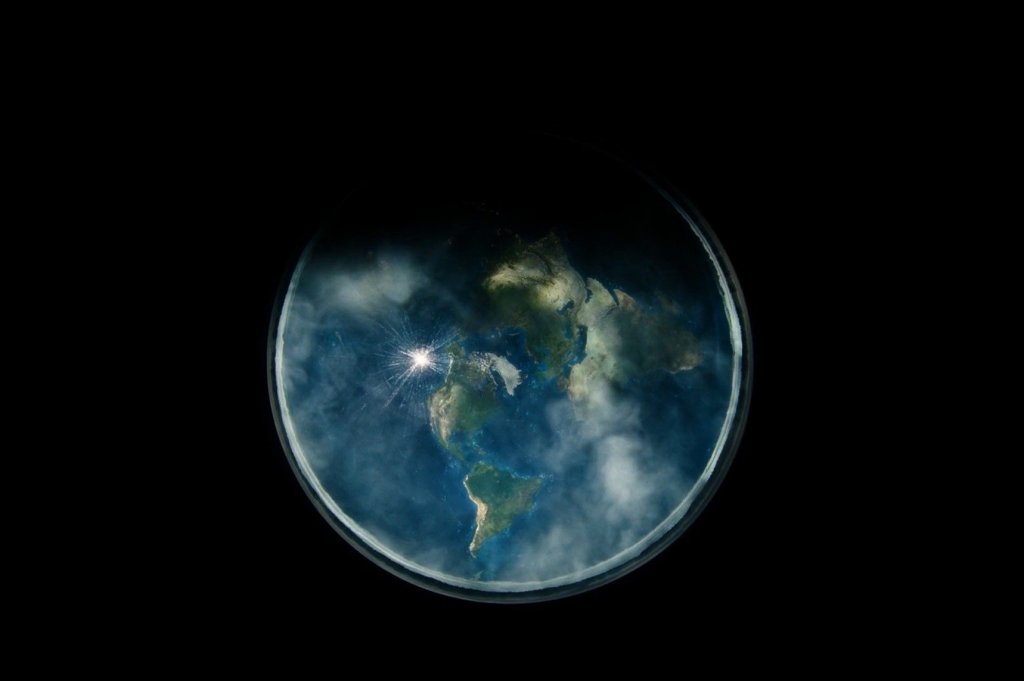

By the end of the film, Man-su gets everything he wanted. He keeps the house, his family is happy once more, and he is the new manager of Moon Paper’s first automated facility. All that bloodshed and for what? A menial job overseeing the AI powered paper machines. A middle manager without a team to manage. Man-su’s job, his life’s work, hollowed out and sold back to him. As he smiles to himself on the lifeless, factory floor, I shudder. Disgusted by the lengths we will go in the dehumanization of ourselves and others for little more than a slightly nicer pair of shoes.

For as grim and upsetting as the subject material is, it is worth noting that watching a hapless man stumble over his own feet, and just barely avoid getting caught is extremely funny. Misunderstandings, false accusations, and close calls make the second act of this film as tense as it is hilarious. An incompetent, non-killer has to buck up courage he doesn’t have because he’s convinced himself that there’s nobility in his actions since it’s for his family.

Lee Byung-hun the, recently Golden Globe nominated, actor who plays Man-su perfectly captures the fear and indecision in his eyes when faced with these life and death choices. He’s not a killer by nature so part of the fun is watching him overcome this internal conflict. You can see it in his face where he is actively reconciling with his actions and making excuses in real time. There’s not a bad performance among this cast, but Lee deserves the recognition he’s getting and more.

Then there’s Jo Yeong-wook’s haunting score of reverberating cello notes, fading in and out of the background. Blurring the lines between diegetic and non diegetic sound, it’s disorienting in an exciting way, never clear if what I’m hearing in the score will soon be revealed to be Ri-one hard at work, practicing upstairs.

The editing is similarly dizzying and dreamlike. This year, I’ve focused on watching mostly films from the 20th century. In that, I developed a growing pet concern over the absence of dissolves in 21st century cinema. The longer the year has gone on, the more my frustration has grown so thank goodness for No Other Choice which has dissolves in spades. A delightful spectacle, made even better by seeing this in IMAX.

One of the most formally impressive films of 2025, full of deliberate and specific directing, editing, and camera choices that I don’t think I’ve ever seen before. Park Chan-wook’s been at this for a while so it shouldn’t be a surprise, but it’s rare to witness such mastery over the craft, while still having a ton of fun smashing his characters to bits.

Leave a comment