The Wild Robot is an animated adventure film about survival, parenthood, and overcoming the perceived limitations of one’s biology. The film is adapted from the children’s novel of the same name written and illustrated by Peter Brown. Brown received critical acclaim for The Wild Robot, which landed on several “Best of 2016” lists and became a New York Times Bestseller. Chris Sanders was chosen by DreamWorks to helm the project after the company acquired the rights to adapt Brown’s book.

Sanders is a prolific filmmaker in animation who got his start working as a storyboard artist and character designer for Disney during the renaissance era. He helped develop classics like Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, The Lion King, and Mulan before CEO Michael Eisener took a chance on a character pitch Sanders had since 1985. Sanders was offered to develop this character further, landing his first directorial feature, Lilo & Stitch. He would go on to voice the character of Stitch in nearly every sequel and spin off. By the mid-2000’s, Sanders began his departure from Disney and was courted by DreamWorks to write and direct the widely beloved film, How to Train Your Dragon. With two of the most influential animated films of the 21st century under his belt, Sanders was an obvious pick for The Wild Robot.

After a storm causes a Universal Dynamics cargo ship to crash on the coast of an untamed island, the sole surviving robotic unit emerges from the wreckage in search of the customer who ordered her. ROZZUM Unit 7134, played by Lupita Nyong’o, nicknamed “Roz” wanders haplessly around the island, seeking a designated task and purpose, but is unable to communicate with the forest animals. She updates her language processors in order to better understand the needs of the island’s inhabitants, but is disappointed to learn that all of the animals fear her. With no tasks to complete, she fires up a retrieval signal to be returned to the factory she came from. But a bolt of lightning strikes, frying her communication beacon, and in a panic she flees accidently crushing a goose nest in the process. One single egg remains and Roz makes it her responsibility to keep it from harm’s way.

A hungry fox named Fink, played by Pedro Pascal, has other plans however. The two battle it out for the unborn goose, with Roz eventually claiming the egg for herself. Upon hatching, the gosling, named Brightbill, imprints on her, treating Roz as his new mom. Realizing that the naive robot can be manipulated into providing him food and protection, Fink forms an unlikely friendship with Roz and assists her in raising Brightbill. In order for Roz to complete this new task, she needs to ensure that Brightbill is able to eat, swim, and fly, the essential skills every adult goose needs. But parenthood is more art than science, proving difficult for Roz who was not programmed with these skills in mind. The found family dedicates their time to ensuring Brightbill is ready for the upcoming migration. However, this bond is threatened when Brightbill discovers that Roz is accidentally responsible for the death of his biological family.

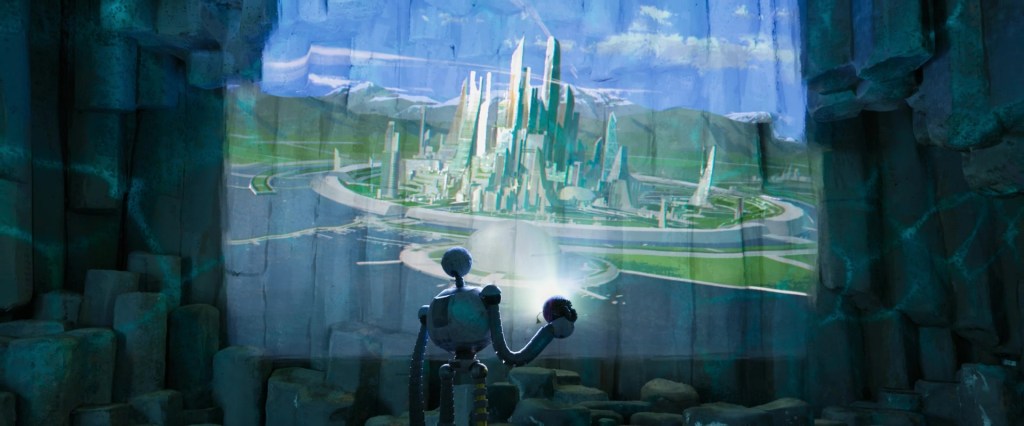

It is easy to get swept away by the vivid watercolor textures and natural vistas of The Wild Robot’s world. The film draws stylistic inspiration from Disney animated classics and the work of Hayao Miyazaki. The forest environments of the island were heavily inspired by the hand painted backdrops of Bambi and My Neighbour Totoro. Sanders was dedicated to creating a film where the final result still resembled the concept paintings used in development.

Even the character models, which were constructed using standard CGI animation, received a final top coat of texture to resemble brushstroke lines. It captures the storybook quality of the source material, giving the film a unique look unlike the repetitive realism that has become the dominant style in the medium. The colors pop, the character models are dynamic and expressive, and the environments are breathtaking. The setting and characters are deceptively simple, something we’ve seen time and again in films for children, but The Wild Robot distinguishes itself from its peers by pushing the boundaries of 3D animation. Simply one of the best looking films of the year.

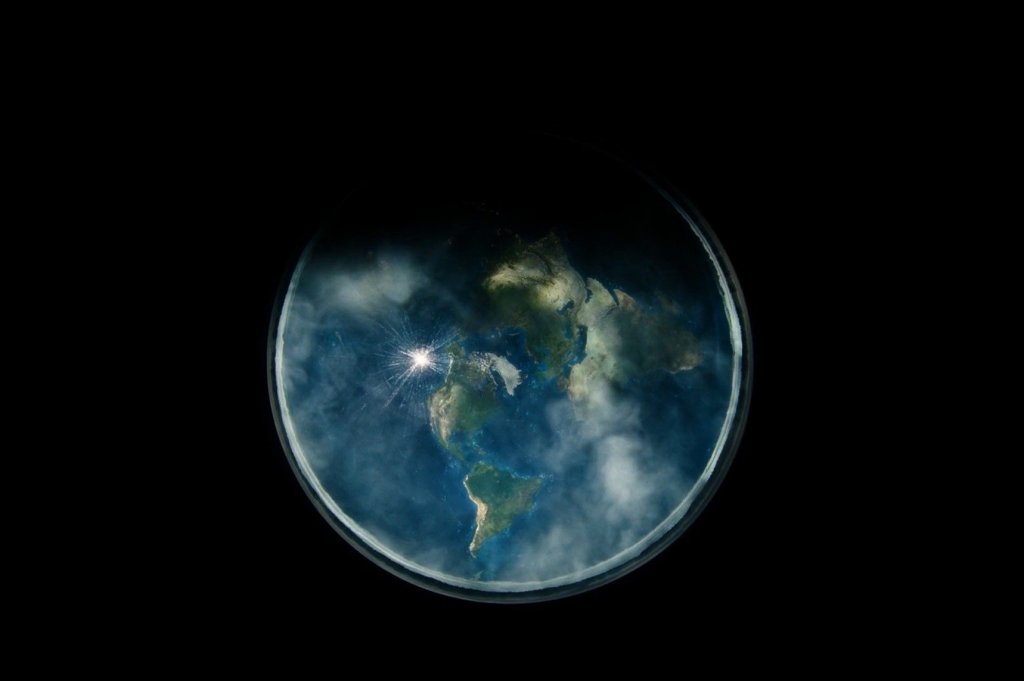

The Wild Robot’s success is in part due to how much of the story is communicated through its visual language. It’s set in a near future where autonomous worker robots are a reality, yet most of the film takes place in a remote setting. The disconnect between the natural and manmade worlds are central to understanding The Wild Robot. During the film’s pivotal migration sequence, the state of the rest of the planet is revealed to the audience in glimpses. A startling moment shows the Golden Gate Bridge partially submerged in the bay, with a pair of whales gliding past it with ease.

The environmental impact is not explicitly stated, yet the implication is clear that climate change has resulted in rising sea levels. The instability of the environment is also referenced with the storm that shipwrecked Roz and the blizzard that threatens life on the island during the Winter months. The first humans we encounter live in isolated cities of the future that are largely built to protect their citizens from these emerging natural disasters. The other ROZZUM Units that live alongside humans are primarily responsible for securing the food supply. These farms are also shielded from the outside world in large geodesic domes.

However, the animals live far removed from any human activity. They have no frame of reference for the world that Roz comes from, and interpret her helpfulness as a threat to navigate. Her arrival on the island results in chaos for the animals, fearing she is a monster sent to kill them all. Their assessment of her intentions are incorrect, but justified by her clumsy mad dash that results in the death of Brightbill’s family. The technological advancement that she represents is synonymous with the shrinking of their world.

The island Roz finds herself stranded on is completely foreign to her as well. ROZZUM Units are built to complete assigned tasks, jobs provided by the humans who invented them. So what happens when there’s no humans to delegate responsibilities to her? This is something Roz struggles with early on. Upon meeting Brightbill, she determines that her task is to properly raise the gosling to adulthood. A task that it is not easy to define so with the help of Fink, she breaks it down to three achievable steps. However, this job is unlike anything she was programmed for. Roz is not equipped with the ability to respond emotionally, at least not in the ways that parenthood demands. She surprises herself in moments where she becomes protective over Brightbill, even fearful of the journey ahead which he must make alone. Nothing in her code instructs Roz to develop these feelings, yet she does anyways.

At the heart of The Wild Robot is the idea that each of us can rise beyond the circumstances and limitations of our lives. In pursuit of accomplishing her task, Roz rewrites her code on the fly to be able to improvise and become a surrogate mother for Brightbill. She does this based on her initial programming, but in the process frees herself from the confines of her code. This is not something she does intentionally or with the express purpose of becoming a better parent, rather it grows organically from her love for Brightbill. With her guidance and newfound empathy, she shepherds the young goose into achieving what was thought to be impossible.

Brightbill similarly is the runt of his family, never meant to survive on his own. His small stature and failure to thrive would have sealed his fate early on had he never met Roz. In the unforgiving natural world, Darwinism rules. Nothing in Brightbill’s biology would suggest he makes it to adulthood, much less lead a successful migration. Even when he’s distraught upon learning his family’s fate, even when the other geese ostracize him, he never gives up. Refusing to fall into despair over the circumstances of his birth, he sets out to defy expectations.

Then there’s Fink, who had resigned himself to a life of quiet misery on the outskirts of the forest’s social hierarchy. Mistrusted and feared by all, he gave into this perception becoming the very animal the others decided he was. He keeps everyone at a distance, never knowing friendship or love. Easier to be feared than it is to be hurt. Fink doesn’t show how this alienation has affected him, but it clearly has shaped his own sense of self entirely. Rather than rising above their prejudice, he gives in, without expectation that he could become anything else. Then he meets Roz, who lacks the same judgments that the other animals possess. She trusts Fink to help raise Brightbill, despite the danger of keeping a fox around a newborn goose. No one has ever afforded him that much grace, acceptance, and understanding before. Thus giving Fink the opportunity to prove to himself that he’s not the fox everyone thinks he is.

Early on, Fink cynically chastises Roz for her naivete and willingness to trust him. “Kindness is not a survival skill.” A philosophy garnered from a life of competing for resources and avoiding becoming someone else’s meal. While this ruthless worldview has some merit for surviving conditions in the wild, it is not sustainable for the collective wellbeing of all the animals. Eat or be eaten no longer works if there’s no one left alive. During a deadly winter storm, Roz and Fink set out to rescue the other animals whose dens are buried under piles of snow. They return them to Roz’s makeshift shelter where they can warm up by the fire. However, all of those predators and prey animals under one roof proves to be disastrous.

Fink puts an end to their fighting by reminding the animals that none of them would be alive without the help of Roz. The robot who they all made fun of, stole from, and wrote off as a monster. Her kindness, her willingness to look past their discretions is the very thing keeping them all alive. Before shutting down, Roz requests that the animals put aside their natural inclinations and form a truce, just until the end of winter. The group settles in for season and emerges in the spring alive and better off for their time spent with the robot.

Does our genetic makeup determine our destiny? Every one of us is programmed to survive. To keep ourselves and our immediate loved ones alive, often at any cost. This impulse is typically portrayed as a positive one, the reason our species continues to thrive. However, in a world where scarcity of resources drives competition between humans, these baser instincts have had catastrophic consequences for the most vulnerable among us. Lack of access to these resources, whether food, shelter, or wealth, is treated as a failure of the individual rather than the collective. Their inability to secure their own survival is not the responsibility of anyone else. This is especially the case when these failures are linked to something innate about the individual. This attitude has been historically weaponized against marginalized groups. Whether it is towards other races or people with disabilities, Darwinism has been used to justify some of the worst atrocities committed by people towards people.

When the other geese are ready to let Brightbill die because of his physical and cultural differences, we see the harm this worldview inflicts. If they were successful in ostracizing him from the flock, none of them would’ve survived the migration. The willingness to look past one’s own prejudices, fears, and selfish concerns is a necessary skill to survive the incoming challenges that will affect us all. None of us survive on our own. We must rely on the trust and compassion of one another to continue forward. We cannot afford to right off kindness as a frivolous ideal that has no place in reality.

Leave a comment