Inside Out 2 is an animated coming of age story about growing up and processing all of the new and complex emotions associated with adulthood. The film is a sequel to 2015’s Best Animated Feature winner, Inside Out, taking place just two years later. It’s Kelsey Mann’s directorial debut after serving as story supervisor and working with Pixar’s extended creative team since 2013’s Monsters University. After the commercial and critical success of the original, a sequel to the beloved film was inevitable. When conceptualizing the follow up, Mann returned to the initial film’s source material, a study conducted by the University of California, Berkeley which determined that there are 27 basic emotional responses. This idea was foundational to the original movie, but the nuance’s of this study were simplified in order to create the five distinct characters audiences grew to love: Joy, Sadness, Anger, Disgust, and Fear.

Mann’s first draft of Inside Out 2 included nine new emotions who would outnumber and overwhelm Joy. As the amount of characters became challenging to keep track of, he paired this down to just four new emotions: Anxiety, Envy, Embarrassment, and Ennui. Two emotions left on the cutting room floor, Guilt and Jealousy, were incorporated into the characters of Anxiety and Envy, taking over the scrapped emotion’s associated story elements.

The film follows Riley who is now on the cusp of entering high school, enjoying one last summer with her friends before they head off to different schools in the fall. The night before Riley’s set to start hockey camp, Joy and the other emotions are awoken to a total renovation of headquarters. The console, which they use to help Riley navigate the world, has been upgraded and expanded. The purpose? To make space for Riley’s new emotions who will help guide her through puberty and the complicated social hierarchy of high school. Envy helps her identify what she needs to fit in with the older girls at hockey camp. Embarrassment helps her avoid uncomfortable social interactions and scenarios. Ennui gives her the sarcastic, disaffected edge needed to appear cool and downplay any faux pas. But most consequential of the bunch is Anxiety who is responsible for keeping Riley safe from potential disastrous outcomes by constantly thinking ahead.

Having learned her lesson from the first film, Joy meets these new emotions with about as much enthusiasm and empathy as she can stomach. As she first did with Sadness, Joy does not immediately see the value in these emotions. Watching Riley experience discomfort as a result of their actions does little to inspire confidence. While Joy has grown since we last saw her, she can’t help herself when it comes to wanting to prevent Riley from experiencing anything negative, no matter the degree or intensity. She has even developed a tool which discards any uncomfortable memory by launching them to the back of the mind, where they will be forgotten forever.

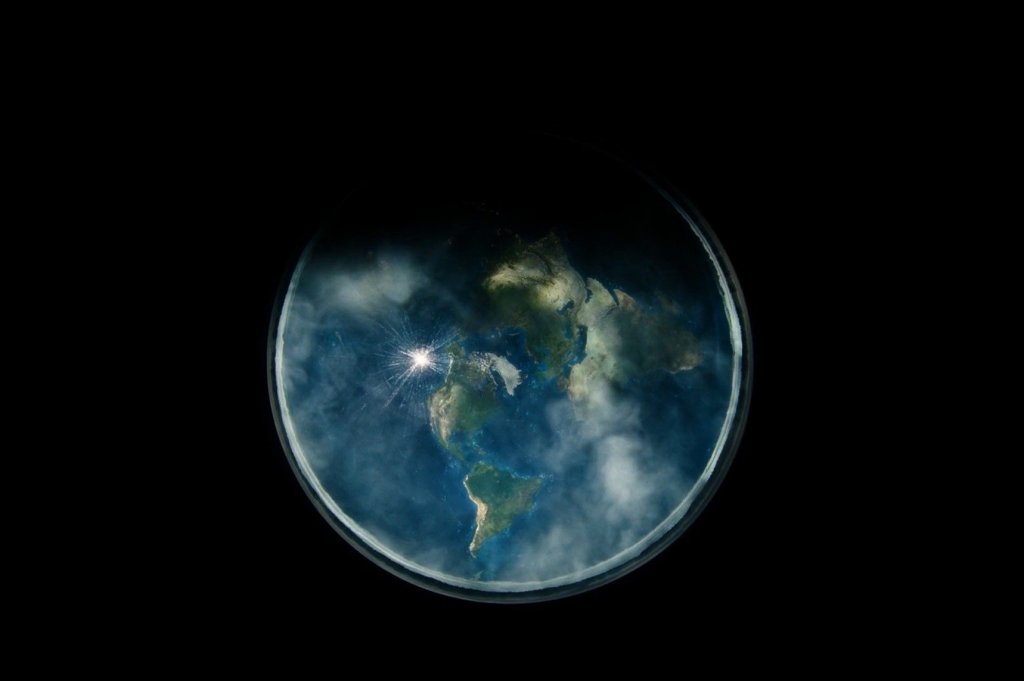

As Riley has grown up, she’s developed a more sophisticated system which represents her personality. Previously, this was defined by five core memories which made up five floating “personality islands.” These are still present in the sequel, although “family island” has since been dwarfed by “friendship island.” However, Riley’s emerging adult personality is too complex to be defined solely by these islands alone. In their place, a sublevel of core memories was constructed. Each memory stored here takes the form of a belief, a truism born out of Riley’s experiences: “I’m a really good friend,” “I’m a winner,” and “Homework should be illegal,” to name a few. Together they create an interwoven belief system which makes up Riley’s sense of self. A guide stone that helps Riley navigate the world and take actions that align with who she is.

Inside Out stunned audiences the first time around with its brilliant visual metaphors. The belief system and sense of self build upon and supersede the groundwork laid by the original film. It takes the complicated, theoretical, and somewhat metaphysical idea of personhood, what it means to be “you,” and simplifies it perfectly to be understood by audiences of all ages. Experiences, more specifically our memories of those experiences, shape our beliefs, dictating how we feel about ourselves, others, and the world at large. These beliefs can be changed or molded, but only after new experiences challenge our existing ideas. Together, our beliefs make up who we are or at the very least the perspective we filter the world through. All of the positive memories that Joy has cultivated over the years have led Riley’s internal voice to proudly announce, “I’m a good person.”

It’s a remarkable distillation of what it means to be a person, delivered in a way that can be understood by adults and children alike. Part of what made Inside Out so successful in the first place is how it was utilized as a tool to help parents talk to their kids about their feelings. Personifying their emotions as a way of understanding them better. Here, it takes it a step further by introducing important questions about how we see ourselves in relation to the world around us. Inside Out 2 asks its audience to question how we form our opinions and whether they represent reality accurately or not. Our emotional responses to life’s experiences are intrinsically linked to these beliefs.

It’s a bit trite to say that the latest Pixar film is visually impressive, but the animators have really outdone themselves in how all these ideas are represented on screen. The belief system alone, is one of the most awe inspiring images and environments of the year. When Joy and Sadness first revealed this new location, I was left speechless. Simply a stroke of genius.

Anxiety has big plans for how to help Riley perform well enough at hockey camp to secure a spot on the high school team. Part of this plan involves working through every possible negative scenario in order to prevent these outcomes from coming to fruition. Joy is unwilling to relinquish control of the console, still believing she knows what is best for Riley. Joy encourages her to goof around with her friends in the locker room, only to get caught by the coach who makes everyone give up their cell phones and do laps around the rink as punishment. Riley is humiliated in front of everyone and hurts her chances of being recruited to the Fire Hawks. Realizing that her current personality will not serve Riley in achieving her goals, Anxiety removes the former sense of self and launches to the back of the mind as Joy had previously done with unwanted memories. Anxiety, unwilling to let Joy ruin this opportunity, then orchestrates a coup, exiling her and the older emotions from headquarters.

Joy and company are bottled up as “suppressed emotions” and sent away to Riley’s vault where secrets are stored under rigorous surveillance. The crew must hatch an escape plan and journey to the back of the mind to retrieve Riley’s sense of self. In the meantime, Anxiety gains full control over the console and does everything in her power to prevent further disruptions to their plans. To do so, she introduces more core memories to the belief system, which will help shape Riley’s new sense of self.

Anxiety is driven by a relentless pursuit to avoid future pain, by catastrophizing every small decision Riley makes. While not rational, this frantic impulse comes from a place of wanting what is best for Riley. The same thing that Joy wants. It makes for a fascinating antagonist who while destructive in her actions, is honest in her motivations. She encourages Riley to ignore her old friends, not from a place of cruelty, but out of a need to secure a social group so she isn’t forced to eat lunch alone on her first day of high school. Anxiety pushes Riley to be the best she can be at hockey, not to see her crumble under the pressure, but so she is set up for success later in life. However, this cultivation of a new Riley has unintended consequences.

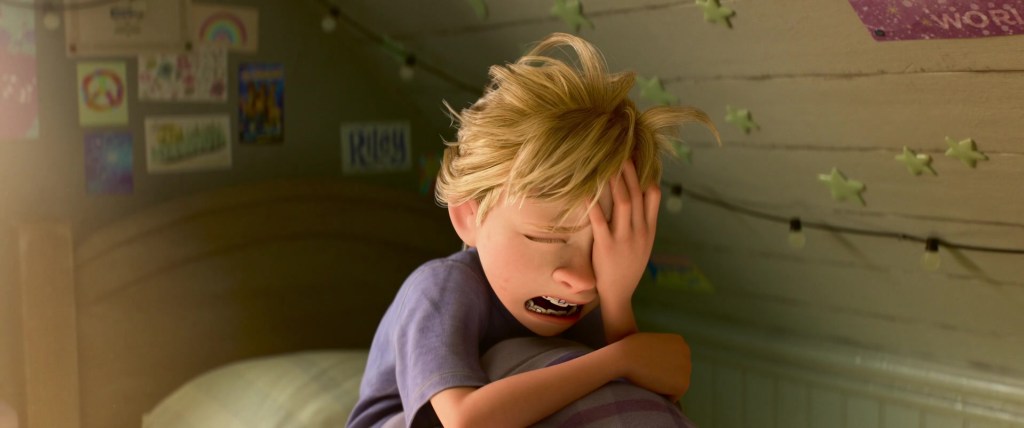

The night before the final game, Anxiety hijacks Imagination Land, a metaphorical movie studio responsible for Riley’s creativity. She has all the concept artists there working overtime to produce possible negative projections on how Riley could lose the game. These ideas are broadcasted to Riley as racing thoughts while tossing and turning in bed. Aside from the belief system, this is my favorite abstract visualization in the entire film. It captures the feeling of laying awake at night, tormented by thoughts of disaster and failure, perfectly.

Beyond that, it succinctly defines this manifestation of anxiety as “using Riley’s imagination against her.” Rather than imagination being the impetus for creativity and wonder, it is weaponized as a tool to ruminate on worst case scenarios. Joy’s solution to counteract Anxiety’s misuse of Imagination Land is by introducing a series of (just as unlikely) positive scenarios. This is a real and practical coping mechanism to deal with irrational and fear based thought patterns. This is a skill that many adults do not possess so presenting it to a primarily young audience, empowers them to take control over these overwhelming feelings.

As she fills Riley’s head with panicked thoughts of inadequacy and potential failure, a new sense of self forms. One that no longer states, “I’m a good person,” and instead says, “I’m not good enough.” This sends shockwaves through Riley’s brain just moments before the final camp scrimmage, the game that will determine if she makes the team or not. Rather than being motivated by her love of hockey, this new personality is coming from a place of fear and doubt. Riley then overcompensates during the game by hogging the puck, refusing to pass to teammates, and ultimately receiving a penalty for checking her old best friend, knocking her on the ice.

This was not what Anxiety had envisioned when she began creating Riley’s new self. She quickly saves face and assures the other emotions that this new core belief will help Riley succeed, by encouraging her to continue improving herself. Not even Anxiety is convinced of this though. When Riley ends up in the penalty box, she loses control over the situation. Anxiety and by extension Riley begin to spiral out, believing all their hard work will have been for nothing if they don’t secure their spot on the team.

Anxiety triggers a full on panic attack and reaches a state of such heightened emotions that the others are unable to remove her grasp on the console. It is a surprisingly honest depiction of an anxiety attack, visualized as a full on executive malfunction. Anxiety races around in circles as the “I’m not good enough” belief rattles around in Riley’s brain. The panic locks Anxiety in this frenzied blitz, the scenario she was trying to avoid throughout the entire film has now arrived. She cannot relinquish control, even if she wanted to, and even if that would likely be what’s best for Riley. Too far gone and unreachable, part of Anxiety’s meltdown comes from recognizing that her actions directly led to this outcome.

I cannot imagine how impactful this scene would’ve been on me as a child. Growing up with a panic disorder and lacking the language to describe it, led to years of dismissal both internally and externally. Inside Out 2 expertly conceptualizes anxiety attacks and gives the audience the tools to understand what is happening to them when they’re in the midst of confronting these nervous outbursts. Anxiety’s behavior in this scene perfectly captures the racing thoughts of self doubt and fear as she runs laps around the console creating an impenetrable behavior with her frenetic movements. When Joy is able to break through this wall, it is revealed that Anxiety is attached to the control levers, but unable to move. Frozen in place, gripping as hard as she can, and yet is unreachable. Joy attempts to pull her away, but is unable to touch Anxiety who flickers in and out of tangible space.

The film continues its masterful visual metaphors by highlighting the seemingly conflicting nature of anxiety. Sometimes it produces boundless energy, sometimes it causes paralysis, and other times it is both. When Anxiety is finally removed, she apologizes to Joy, stating that she was just trying to protect Riley. Her and Joy both realize that they have been imposing their will onto who Riley is, when it is not their place to make that decision. The new, anxious sense of self is removed, but not replaced by the old as Joy had intended. Instead, all the core memories work to create a sense of self that accurately reflects the person Riley has become. One that is multifaceted, able to hold contradictory beliefs, and more willing to understand and accept her gifts and limitations.

The new sense of self is less rigid and as a result more realistic to how real people interface with the world. It is possible to be both a good friend and a selfish person. To want to fit in with the crowd, but be true to yourself. To believe you’re not good enough, but wanting to try your best anyways. It would be so simple to be defined by just one of these core beliefs, or to have them align neatly with how we’d like to present to the world, but these contradictions make us who we are. Our experiences become memories and those memories can change with time and perspective. It’s these contradictions that help us change course as life presents us with situations that test our beliefs.

The resounding message behind Inside Out 2 is that while we can’t force ourselves to be something we’re not, who we are is multidimensional. Our personalities are fluid and malleable, able to change when faced with all the adversity, conflict, and pleasure that life has to offer. As we grow older, there’s less capacity for joy. Life gets harder, the answers to issues don’t come as easily, and the pressures of the world compel us to fall in line or despair about the circumstances. These difficulties and moments of pain are just as valuable as they test our resilience and reinforce our understanding of the self. It builds empathy for others, exposes our vulnerabilities, and as a result reveals what actually matters to us. It is easy to trap yourself in an endless spiral of negativity and fear, but we mustn’t ever give up on joy.

Leave a comment