Dìdi is a coming of age, teen comedy about the son of Taiwanese immigrants navigating the cultural landscape of California’s Bay Area during the onset of early social media. It is the feature directorial debut from filmmaker Sean Wang. His previous work Năi Nai & Wài Pó, a documentary short about the relationship between a paternal and maternal grandmother, won the Grand Jury and Audience Award when it premiered at South By Southwest in 2023. It also secured an Academy Award nomination for Best Documentary Short Film. Following his success last year, Dìdi premiered at Sundance Film Festival where it won the Audience Award: U.S. Dramatic and U.S. Dramatic Special Jury Award: Ensemble. It was recognized by the National Board of Review in the top ten best independent films of the year.

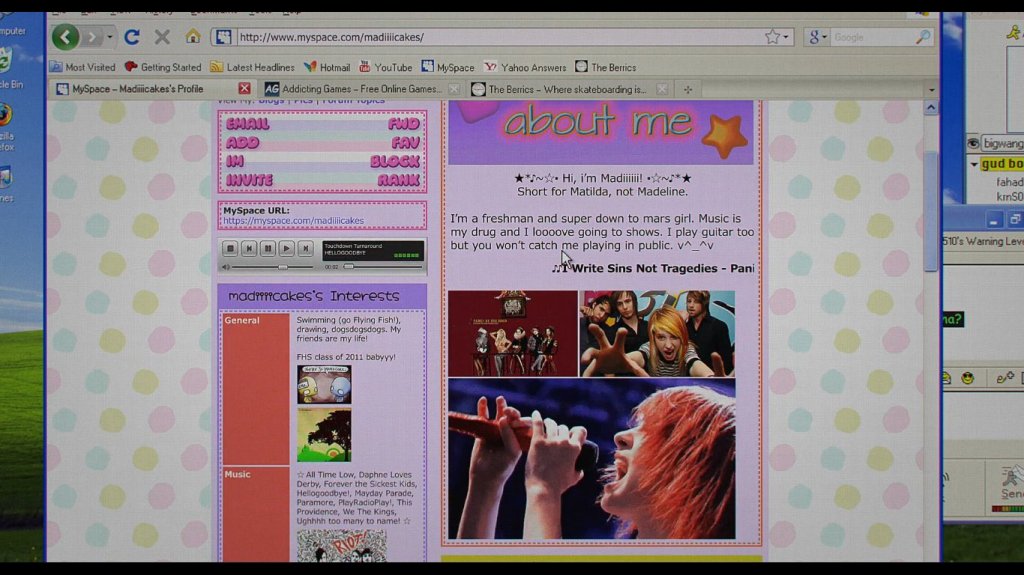

The film stars relative newcomer Izaac Wang as Chris, the titular Dìdi, or little brother in Mandarin Chinese. This is the young actor’s first lead role, receiving a nomination at this year’s Gotham Awards for Breakthrough Performer. We meet Chris during the summer between eighth grade and high school, a transitional period where friends come and go, crushes on girls form, and the ever present allure of the computer screen shapes one’s sense of self. It’s 2008 which means that, while the smartphone has yet to take over the world, Facebook, Myspace, YouTube, and AIM have brought upon this new wave of online media that teenagers must learn to navigate blindly. It’s an entirely new frontier, giving kids the tools to communicate, lash out, and discover who they are. When he isn’t with his friends, Chris spends much of his day clicking through YouTube skits and skate videos, wondering how he could one day produce videos of his own.

Chris lives with his immigrant mother, Chungsing, her nagging mother-in-law Nai Nai, and his older sister Vivian. Chris’s father is absent from the film, working in Taiwan and sending money back to support his family. Three different generations living under one roof naturally leads to conflict. Nai Nai and Chungsing argue over how the latter is choosing to raise her children in America. Nai Nai pushes for more traditional and rigorous means of education to guarantee both Chris and Vivian have the best possible chance at success in their careers and with their future families. To her, ensuring this legacy is vital as she confronts the end of her life. Chungsing defends her choices, by reminding Nai Nai that she is raising both children without the help of her husband. She cares about their success too, but the focus is much more about their happiness as individuals. However, Chungsing does not quite understand the pop culture world and emerging social media environment that her children have grown accustomed to.

Their desire to assimilate into American culture, fueled by the need to fit in with their peers, frequently puts her on the outs with her own kids. It’s not that she faults them for this desire to be accepted, but it makes it challenging for Chungsing to connect with them and relate to their interests. Chungsing must navigate these cultural hurdles, all while maintaining her home, raising her children, and finding personal fulfillment wherever she can.

Since he’s thirteen years old, Chris is naturally insecure about his relationships with others which not too long ago felt so simple. His best friends Fahad and Soup are becoming less interested in their boyhood pastimes, eager to mingle with a new social group, and hookup with girls along the way. Chris, who seems more than happy to continue making ridiculous prank videos with his buddies, is suddenly out of his depth. He doesn’t have experience talking to women, outside of his three overbearing family members. And despite Chris’s attraction to his classmate, Madi, he only really pursues her out of peer pressure. Fahad encourages him to ask Madi out, hoping to get his best friend laid in the process, without considering that Chris hasn’t even kissed a girl before, nevermind anything beyond that. It makes him incredibly uncomfortable, and Chris frantically constructs a new set of interests that he thinks will win Madi over: Changing his ringtone to “Touchdown Turnaround” by Hellogoodbye because it was Madi’s Myspace profile song. Wearing a Paramore shirt to the party she’s attending, knowing Hayley Williams is her favorite artist. Deciding A Walk to Remember is his favorite movie, despite having never seen it, simply because it was listed on her Facebook profile as one of her’s.

All of this works to get her attention, but when they finally spend time alone, it becomes clear to Madi that Chris will agree to anything she says just to have an opportunity to continue speaking with her. She tests his knowledge of movies, forcing him to admit that he doesn’t actually know the color of Yoda or what E.T. sounds like and he only pretended to so she’d like him. To Chris’s surprise, Madi likes him anyway. But this romance is derailed when she gives Chris a backhanded compliment, “You know, you’re pretty cute for an Asian.” and tries to recover with an appropriately awkward round of “the nervous game.” When Madi’s hands move up his thigh and her lips graze his cheek, Chris panics, admitting that he is nervous, and flees the date early, losing the game, as well as the girl. Madi attempts to reconcile after the fact, but Chris is too embarrassed to even face her.

The details here are excruciating. The anxious pauses, unsure what to say, so you end up saying nothing at all. Faking your way through a pop culture reference, lest you no longer seem cool, interesting, or desirable. The infamous nervous game, giving teens an excuse, no permission, to touch each other. The humiliation of actually admitting that the near sexual encounter did make you nervous. Painful and specific, conjured up feelings of insecurities I had long since forgotten. Chris makes a Facebook profile, only after Madi asks if he has one. Something I absolutely did when my eighth grade crush asked the same thing. Embarrassing, indeed.

Chris grows reclusive, as it seems everyone around him is more comfortable adapting to this transitional period in life. His sense of humor is now off putting and immature, jeopardizing Fahad’s chances at getting a girlfriend by association. Fahad distances himself, concerned about the social hierarchy of the upcoming high school year. And then he does the unthinkable- he drops Chris from his “top eight friends” on Myspace. For those who weren’t teenagers then, this was huge. Even the order mattered, so removing your best friend from the top entirely? That was a serious action. Definitive even.

With nothing left to lose, Chris sees this as an opportunity to adopt a new identity. He happens upon a group of older skaters who are in need of a videographer to capture highlight reels. Still flailing, Chris exaggerates his ability and knowledge of skateboarding to fit in with his new friends. He lies about only being half-Asian, Madi’s backhanded compliment still ringing in his head. Chris gets invited to a high school party where he smokes weed and drinks for the first time. Willing to make himself sick with substances if it means his older friends will buy the act. But the charade inevitably falls apart.

So much of early teen years centers around this compulsion to try on different friends and identities. It’s an anxious impulse driven by an incessant need to be liked. Everyone of course wants to be liked and to belong, but for teenagers it’s a matter of survival. Chris is desperate for reassurance wherever he can get it, even if he has to lie for it. However, it’s the lying and stifling of his real personality that’s preventing him from having an honest and secure relationship with someone.

Even his family relationships are contentious because he wants to hide his Taiwanese heritage. Chris is embarrassed by his mom’s customs and limited English, going out of his way to be rude to her in front of his new friends. Anything that could be used to potentially other him has to be controlled and subdued. It’s a terrifying way to navigate the world, everything has to be carefully monitored and calculated. You can see the exhaustion in Chris’s face as it eats away at him.

Just on the edges of this teen identity crisis is the quiet story of an artist who sacrificed it all to provide her children a better life. Joan Chen gives a gentle performance that’s the very heart of Dìdi. Chungsing is warm and caring, setting herself apart from the typically domineering and unempathetic mother characters that often plague the coming of age subgenre. She’s always looking to steer Chris in the right direction, but it comes from a place of love, not control. Despite having circumstances stacked against her, she doesn’t take this stress out on her children. Instead, Wang is unafraid to show his fictionalized teenage self as the instigator. Chris belittles her, hides her away from his friends, and mocks her failed artistic pursuits. At times, he is downright cruel, searching for the meanest possible quip to hurl at her. This self critical examination reads like an apology. An acknowledgment that his efforts to create an identity for himself took shape in the form of unnecessary rage and angst. If the worst thing you can say about your mother is that her love for you is embarrassing, you’re actually in a better position than most.

Towards the end of the film, Chen delivers a devastating monologue reflecting on her choices that lead her to a life in suburban California. In this soliloquy, she poses the question, “Is this what my life has amounted to?” An ordinary existence, taking care of children and managing a household, with little to show for it in terms of personal achievement or artistic fulfillment. She questions how different things would be if she hadn’t married Chris’s father and decided to raise a family. Instead, she wonders what it could’ve been like for her to arrive in America on her own and pursue her dreams. Would she have been a successful painter by now?

Chen shows an expert level of restraint in her delivery. Chungsing’s regrets and “what if’s?” never come across as resentment. She assures Chris that the opportunities presented to him and his sister makes forgoing her own dreams worthwhile. It’s a flavor of monologue we may have seen in other films of this type, but not like this. Chen’s thoughtful revelation and Wang’s earnest and specific dialogue elevate this scene far above its contemporaries. One of the very best performances of the year. Throughout Dìdi, it is clear that there is more to Chungsing than most other mother characters in teen films. She has a rich interior life that would go completely unexplored under the guidance of a lesser director. Wang honors her sacrifice by pursuing his own creative dreams and enshrining his mother’s decision on film forever.

Wang brilliantly recaptures the catastrophic stakes of being a teenager. A time where every decision felt like the most important one you’d ever make and every mistake would usher in the end of the world as you knew it. He sets this examination on teen angst against the backdrop of a newly constructed social environment online. One that teenagers of this era grew up alongside, having to adapt to the ways early social media would facilitate relationships. This was long before anyone was critical of it, nevermind aware of its potential harms. It was a brand new frontier of connection and isolation that kids had to figure out for themselves.

It’s a thing of beauty to see your own life reflected back to you. There’s universal truths found in every coming of age story that resonate across generations, but there’s something special when it captures your’s. I am just a year younger than Chris, having gone through a difficult transition period of my own that very same summer. I moved to a new town, started a new school, and had to make new friends. It was the perfect opportunity to start over and explore my identity, an identity that finally matched how I felt, but was too scared to explore in my hometown. Suddenly the box I had found myself in since first grade no longer existed. There was panic, excitement, and plenty of insecurity, but it was freeing once I stopped trying to be the person I thought I was supposed to be. Like Dìdi, my experience also played out while over analyzing an AIM message to a pop punk soundtrack.

Leave a comment