Red Rooms is a sinister psychological thriller about our culture’s morbid curiosity towards true crime narratives and the depravity of one woman who takes her interests too far. It is the third feature film from French Canadian writer-director, Pascal Plante. Red Rooms premiered at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in July 2023, but wasn’t released in the United States until September of this year. It features an award winning performance from Quebec actress Juliette Gariepy as Kelly-Anne, a disaffected model who develops an all encompassing obsession with a high profile murder case.

We open in a sterile courtroom, bright white, harsh, with nowhere to hide. The prosecution states their opening argument against accused murderer Ludovic Chevalier, detailing the depths of his horrific crimes. He is accused of sexually assaulting and murdering three teenage girls. If that wasn’t depraved enough, he recorded and uploaded these acts of violence as videos for sale on the dark web. These are the titular “red rooms,” an idea based on an internet urban legend where acts of murder and torture are freely livestreamed on private servers. Although the existence of such places on the internet are unlikely or at least the rumors are not based on any first hand accounts from law enforcement, the idea is chilling. It’s especially perfect for a thriller about human relationships filtered through screens.

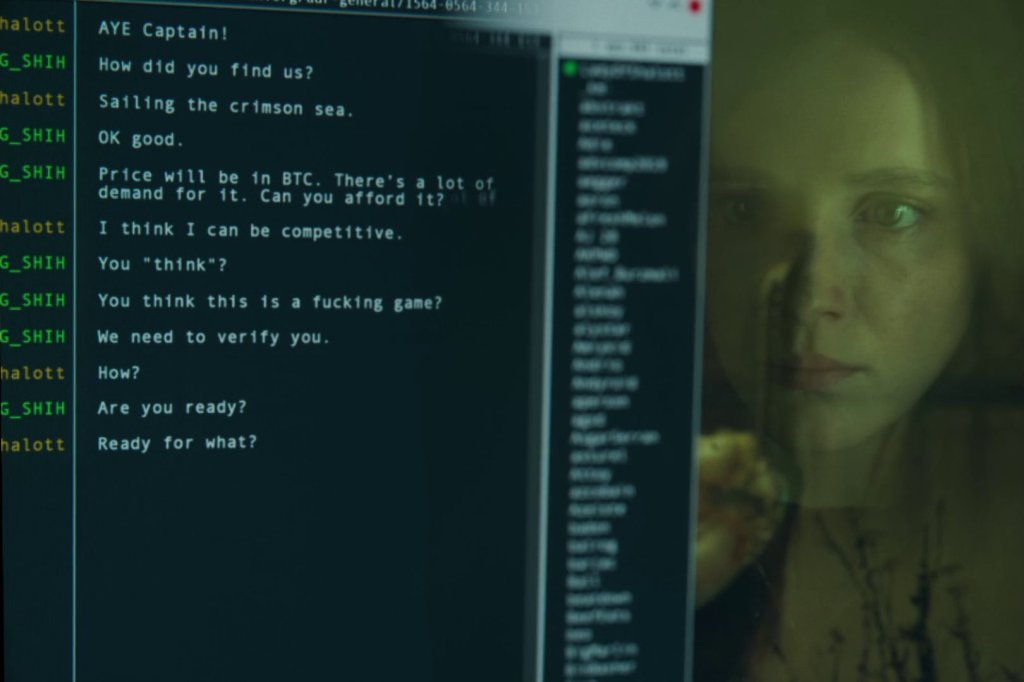

Kelly-Anne spends most of her time in front of the computer. Her screen name is “LadyOfShalott,” a reference to a 19th century ballad by Alfred Tennyson. The poem tells the story of a woman named Elaine who is cursed to spend her life trapped inside a tower in isolation. She must continuously weave images into her loom, but is never allowed to look directly out the window and witness life for herself. Instead, she gazes into a mirror, which reflects the real world back to her. Never getting to see life for herself, forced to view it only as an abstraction. Similarly Kelly-Anne finds herself locked away in a tower, glued to a screen that only depicts a distorted version of reality. Except, it isn’t exactly a curse. Kelly-Anne chose this life in captivity, and even in some ways seems to thrive in it. Whether her affliction occurs to her or not, she doesn’t appear held back by it. Instead, it is the only thing in her life that gives meaning or purpose.

In stark contrast with Chevalier, a homely, middle aged man, Kelly-Anne is not the typical face of evil. In fact, she’s a fashion model. Beautiful, successful in her career, well off financially, and put together. But only on the surface. Her interior life is visually represented by her near furnitureless, glass box of a condo. No living space or kitchen table. All of her meals come from a blender. No personality, scarcely decorated. It’s dim and ominously quiet, except for the gusts of freezing wind that whip past her apartment windows.

When she is not sleeping or at the trial, she’s glued to her multi-screen desktop. Interfacing with various articles on the case, chat rooms discussing it at length, and making her fortune in online poker tournaments. Kelly-Anne’s only source of companionship? An Alexa-esque AI named Guinevere. Her cold disinterest in other people remains a mystery, as does her fascination with the Chevalier murders. Despite living in a luxury building and presumably having disposable income, she chooses to sleep outside the courthouse each night to ensure she is first in line to attend the trial.

This is where Kelly-Anne meets Clementine, a Chevalier groupie who has convinced herself that he is innocent. Worse than that, any evidence to suggest otherwise is deemed fake, photoshopped, or otherwise constructed by the prosecution to defame him. Clementine has more empathy for the man she thinks Chevalier is, than she has for the three victims and their families. While she does not come out and say this, the film’s other characters strongly imply that this is due to a sexual attraction to Chevalier, similar to the attention other serial killers, like Ted Bundy, have received from women. But more importantly, Clementine sees herself in the ostracized murderer. The trial against him is also a trial against her. A woman that is out of step with the modern world, struggling to fit in herself. She finds comfort in her newfound friendship with Kelly-Anne, but doesn’t understand how she can be so sure that Chevalier committed the murders as described.

It would be too easy to have Kelly-Anne be yet another groupie, satisfying a craven crush on a misunderstood man. She’s too intelligent and calculated to fall for such a fantasy, even if she were capable of developing warm feelings towards another person. Three weeks into the trial, the snuff films of the older two girls are to be presented to the jury. To Clementine’s dismay, the judge decides at the last minute that only close friends and family members of the victims are allowed to remain in the room as the evidence is played. Clementine spirals out, needing to see the videos for herself in order to confirm Chevalier’s innocence. Kelly-Anne reluctantly reveals that she has access to both videos, obtained during her activities on the dark web. Clementine admonishes Kelly-Anne’s illegal actions, but nevertheless needs to satisfy her own curiosity. The two view the videos together. Clementine, traumatized. Kelly-Anne, unmoved. Now sure that Chevalier is guilty, Clementine buys the next bus ticket home and never speaks to Kelly-Anne again.

The audience (thankfully) never sees the videos for ourselves. Since the film is criticizing the exploitation of real violence for entertainment, it would be counterintuitive to the core message of Red Rooms to depict even a fictionalized version of these crimes. However, we do hear the videos. The cries for help, pleas for mercy, and tearing of flesh. We see the faces of the two women, Clementine reacting in horror and Kelly-Anne’s analytical fascination with the spectacle. It becomes clear that while Clemetine’s empathy for Chevalier was misguided, at least she actually has empathy. Contrasted with Kelly-Anne who treats the whole ordeal as a numbers game, one of her poker tournaments, what can be gained and who can be manipulated?

Midway through the film Kelly-Anne indirectly reveals her main motivation for involving herself in the trial. She explains to Clemetine the psychology behind winning a poker game, that the real professionals know they can’t rely on luck.

“You have to find emotional players and exploit them. You take your time, you’re patient, and you bleed them dry. That’s what I love, seeing them lose everything.”

“Shit, you’re evil.”

“That’s the game.”

Kelly-Anne, no longer satisfied with exploiting unsuspecting people online, has taken her vile philosophy to the real world. It is not important that she “wins.” She even forgoes her successful modeling career as rumors spread about her daily attendance at the courthouse. Her own professional goals are secondary to the amount of pain she can inflict on others. Everything else in her life is detached and emotionless. The only thing that truly brings her joy is the thrill of seeing other people suffer emotionally, especially if she can witness it anonymously. Kelly-Anne’s hunger for spectacle can never be satisfied and she will stop at nothing to fill this insatiable void.

This all comes to a head in the film’s shocking final act. Unlike the other two victims, the police never located the snuff film for the youngest, Camille. However they found her bloodied school uniform and a jaw fragment with braces attached. Earlier, her mother testified in court, confirming that the items belonged to Camille. Kelly-Anne seeks out an invite only, online sale where Camille’s snuff film will be auctioned off to the highest bidder. After a close call, she narrowly secures the purchase and jumps out of her seat in bliss, smiling ear to ear. The first time she displays a recognizable human emotion. While watching Camille’s murder, she ascends into pure ecstasy. Her single minded ambition finally realized.

But she’s not done yet. In a stunning turn she breaks into Camille’s house, dressed in a school uniform, the very one the deceased was killed in. She pauses to snap a selfie in her bedroom, like a super fan getting an exclusive look. “This is really where she used to live.” An indictment of our self absorbed, clicks driven culture that sees anything and everything as potential content. Camille ceases to exist as a person, her story regurgitated to the gawking masses who will consume her murder just as quickly as they will forget it.

Kelly-Anne leaves a USB by Camille’s mother as she sleeps. She dips out into the night, never having revealed her true identity. The video is submitted as evidence into the trial and with Chevalier’s face clearly visible, the defense decides to plead guilty. Justice is finally served. But at what cost? This outcome is the result of not only the violent death of a child, but one that was recorded and sold for profit. A consumer demand that Kelly-Anne directly contributed to. Then she traumatizes the mother of the victim even further by forcing her to witness the murder. She humiliates law enforcement as the only one to produce irrefutable evidence, by going to the lengths they legally cannot. Flexing her power over them, without even taking credit for it either. That’s not what she wants. Chevalier is sentenced to life in prison, any hope of a lighter punishment is destroyed by Kelly-Anne’s masterful play. She sacrificed her own stability in the process, but regardless achieved the only thing that she loves- “seeing them lose everything.”

Leave a comment