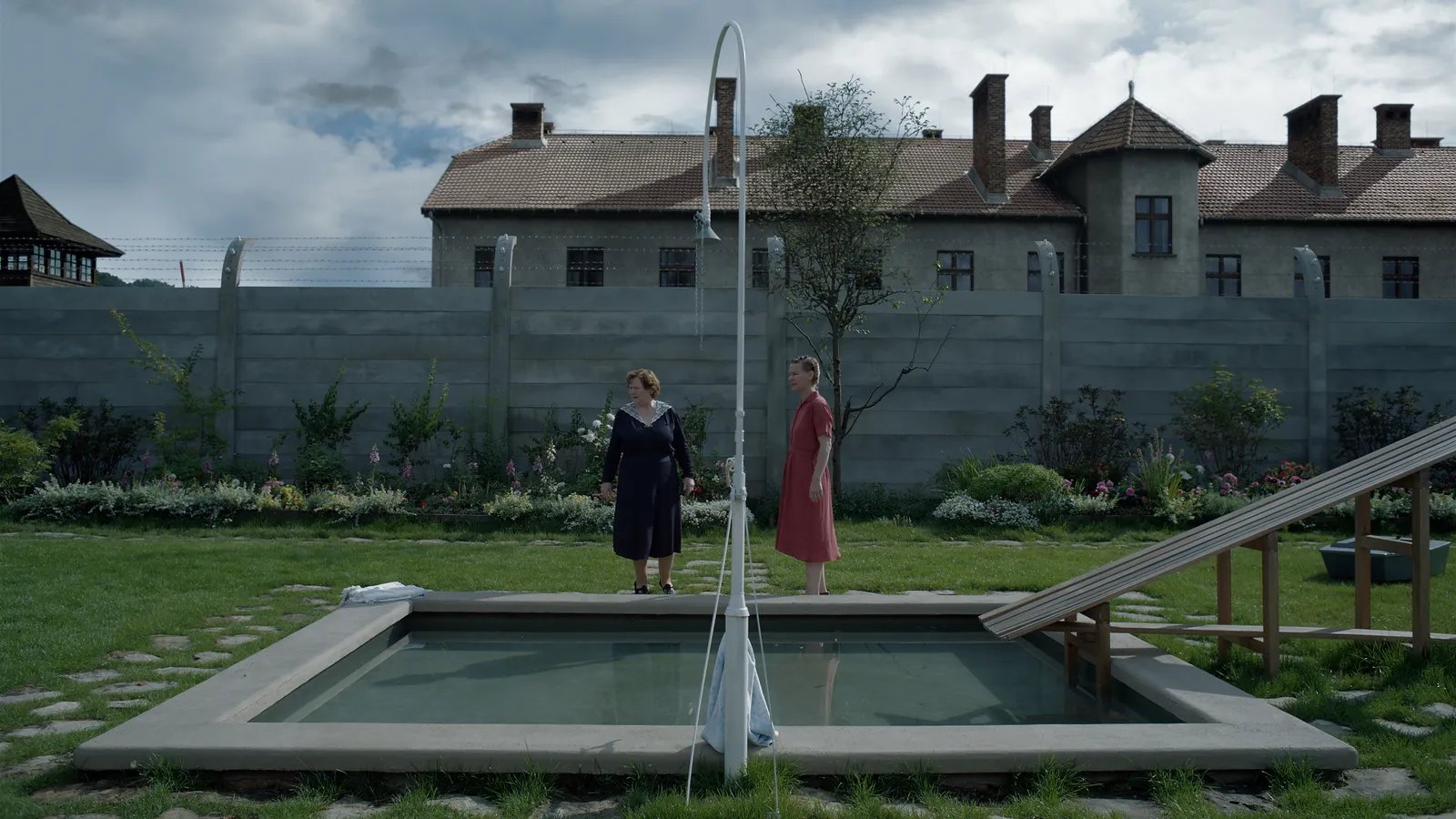

The Zone of Interest is a historical drama that follows an Auschwitz commandant and his family, living in their idyllic homestead adjacent to a concentration camp. Written and directed by Jonathan Glazer, the film is a partial adaptation of the novel by Martin Amis. It premiered at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival where it won the Grand Prix, the Cannes Soundtrack Award, and the FIPRESCI Prize. The film is a significant departure from the source material, only sharing a protagonist who in the novel was inspired by Rudolf Hoss, one of the major architects of the Holocaust. The Zone of Interest stars Christian Friedel as commandant Rudolf Hoss and Sandra Huller as his wife Hedwig. The two have five children together who spend much of their days enjoying their well manicured garden, complete with a swimming pool.

The film opens with a dark screen and a wall of sound, oppressive and omnipresent. Not only does this help to set the stage tonally, it prepares the audience to pay particular attention to the soundscape being created here. As if to say, “brace yourself”. Throughout The Zone of Interest, there’s a constant hum of destruction just beyond the concentration camp wall. It’s as significant of a backdrop as the camp itself. The sound is the only consistent reminder of the horror taking place just out of sight. We hear a steady barrage of gunshots, people screaming in agony, the roar of the towering furnace, and the mechanical pulse of the train transporting Jewish people from across Europe to Auschwitz. However, we never actually see the victims themselves, or even step foot in the camp. Rather than be exploitative and explicitly showing the violence as entertainment, Glazer forces the audience to sit with the sound in their own discomfort. A remarkable feat in filmmaking. At the exact moment we begin to relegate the soundscape to the background, we are jolted awake by a piano sting from the impressive score, perking our ears up once again. An ingenious use of sound design in service of the film’s themes.

By centering the story around a Nazis family and their day-to-day drama, Glazer places the audience in a precarious position. In the years following World War II, film depictions of Nazis have cast them as villains from historical dramas to James Bond and Indiana Jones, and rightfully so. Here the Hoss family is our only point of view into this story and while they are not good people, Glazer asks us to empathize with them on some level. The family is filmed from a mostly voyeuristic perspective, with wide and medium shots keeping a safe enough distance between them and us. But we are not let off the hook that easily. The Zone of Interest challenges us with our own complicity and ability to choose to be blind to atrocities taking place, here literally, in our own backyard. As Hedwig and Rudolf bicker about job promotions, their children’s behavior, and other middle class troubles, thousands are killed daily just a short distance away. It is a deeply uncomfortable comparison, but Glazer asks us to question which side of the wall we’d end up on if such horrible circumstances should arise again. Given the current resurgence of fascist ideology in the Western world, it is an extremely urgent concern for all of us to confront.

This concern is best exemplified by Hedwig’s desire to hold onto her current social position. When we are first introduced to her, she is trying on a mink coat that was confiscated from a Jewish woman who was sentenced to die. Throughout the film we see her proudly show off her prized garden, complete with a team of servants and gardeners, to anyone who will listen. Later, when Rudolf is recommended for transfer out of Auschwitz, Hedwig demands that she stays behind and that her house remains hers. The house by the concentration camp is her middle class dream and she is not going to let it go willingly.

The audience gets the sense that Hedwig is unaccustomed to such luxuries and this disparity in class is perhaps the source of her hatred. This is confirmed when Hedwig’s mother visits her home for the first time and reveals to her that the Jewish woman she worked for for years has been taken away. It is a small piece of the overall film, but it is so effective in showing how class resentments are weaponized against racial and ethnic minorities. A tool that fascists and right wing populists still employ today. During Hedwig’s mother’s stay she develops an irritating and persistent cough. Her sickness startles her awake in the middle of the night and without the distraction from her daughter, she is faced with the billowing smokestack on the horizon for the first time. Hedwig’s mother quietly leaves in the middle of the night, horrified and maybe even ashamed of what her daughter has become.

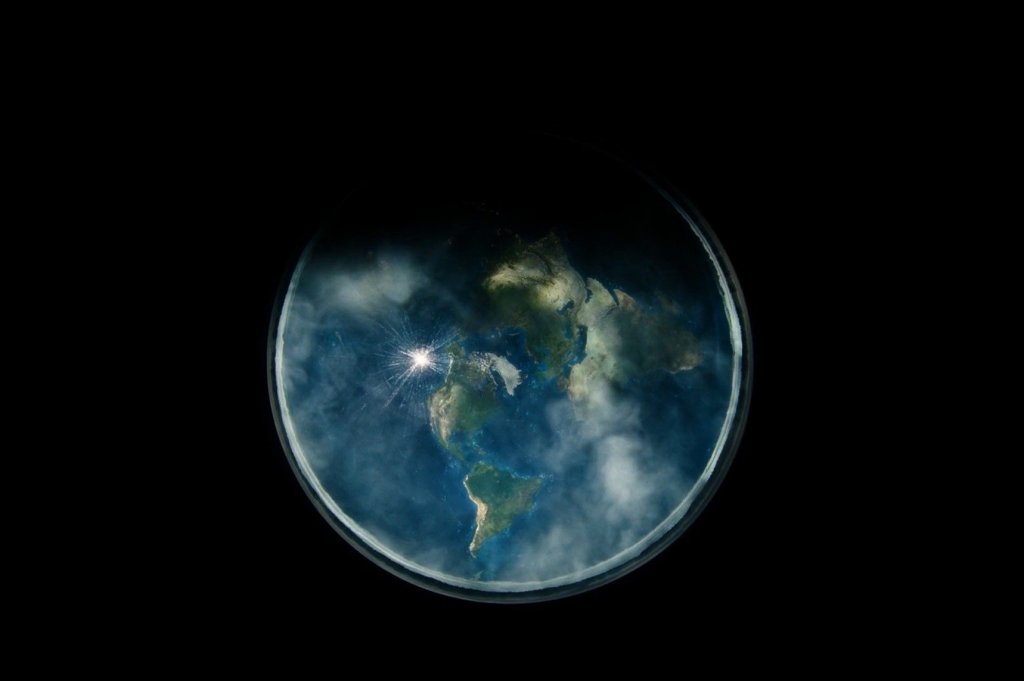

Evil is treated like a sickness within The Zone of Interest, something that has the ability to spread and infect us all. Rudolf is championed by the Nazis party for his role in increasing the efficiency of the death camps. Throughout the film he is seen calculating, the destruction of human life reduced to a math problem. While at a party celebrating his achievements, Rudolf admits that he is preoccupied with thoughts of how to most effectively gas the partygoers. Glazer exposes the inherent irrationality of genocide here, as the violence can no longer sustain itself off of the hatred of a particular group. While Rudolf cannot and should not be redeemed, in the final moments we see a sliver of a consciousness as he retches all over himself, his body finally rejecting the cognitive dissonance and desensitization it embodied in order to carry out his evil actions.

This scene is intercut with shots of workers sweeping and sanitizing the modern day Auschwitz Memorial and Museum. The audience is finally given a glimpse into the interior of the camp, but still from a safe distance of both time and recontextualization. Despite being a direct result of Rudolf’s actions, the images of his victim’s suitcases and shoes on display are not enough to deter him from returning to Auschwitz. It is a bleak reminder that indoctrination, by design, cannot be easily swayed by imagery or appeals to shared humanity. That in spite of our best efforts, the sanitization of history and our failure to learn how “evil” operates has left us woefully unprepared to challenge these ideologies in the 21st century. The Zone of Interest is a chilling film that shakes the viewer out of complicity and demands we reconcile with how violence upholds our comfortable lifestyles, while ultimately acknowledging the limitations imagery has to change behavior.

Leave a comment