Maestro is a quietly devastating film about one man’s struggle to achieve artistic greatness at the cost of his own personal fulfillment. The film is Bradley Cooper’s second directorial feature, after 2018’s A Star is Born, marking a noticeable shift in aesthetic sensibilities while still emphasizing the power of musical performance and the importance of creative legacy. Cooper also stars in this film as Leonard Bernstein, America’s most influential conductor of all time. His work as a musician and composer drastically shaped the landscape of theatre and orchestral performance, influencing the development of classical music during the 20th century. The film’s story centers around Bernstein’s relationship with wife, Felicia Montealegre, played by the incredibly talented Carey Mulligan. The romance between Leonard and Felicia is the driving emotional force of the film and underscores the challenges Bernstein faced as a public figure.

Cooper delivers a career best performance in this role, which can be attributed to the range of creative freedom he possessed as director. However, that has not stopped his film from receiving its fair share of criticism. Earlier this year, the trailer for Maestro appeared on social media which showed Cooper wearing a prosthetic nose for this role. This was considered antisemitic or “Jew-face” to some, sparking outrage in online communities. Bernstein’s own children eventually spoke out stating that Cooper worked with them throughout the entire creative process, up to and including the decision to wear prosthetic makeup. This compounded with a growing distaste for biopics, with critics stating that these films, Maestro included, focus too much on imitation rather than fully embodying the emotional truth of the real historical figure. Additionally, there’s been a pervasive narrative that Cooper “wants an Oscar too much” which has soured some audience members to not only Maestro but Cooper himself. I have grown to loathe the term “Oscar bait” as it has become an increasingly meaningless criticism. The term has become a catch all for any film that puts on the trappings of prestige, but is unable to deliver on its premise in one way or another. I would much prefer a bunch of “Coopers” passionately making films about the power of art that miss the mark or “try too hard” than just about any safe, sterile, but well made film that comes out of the major studios. We are an era that still resists sincerity in filmmaking, but the tide is slowly shifting.

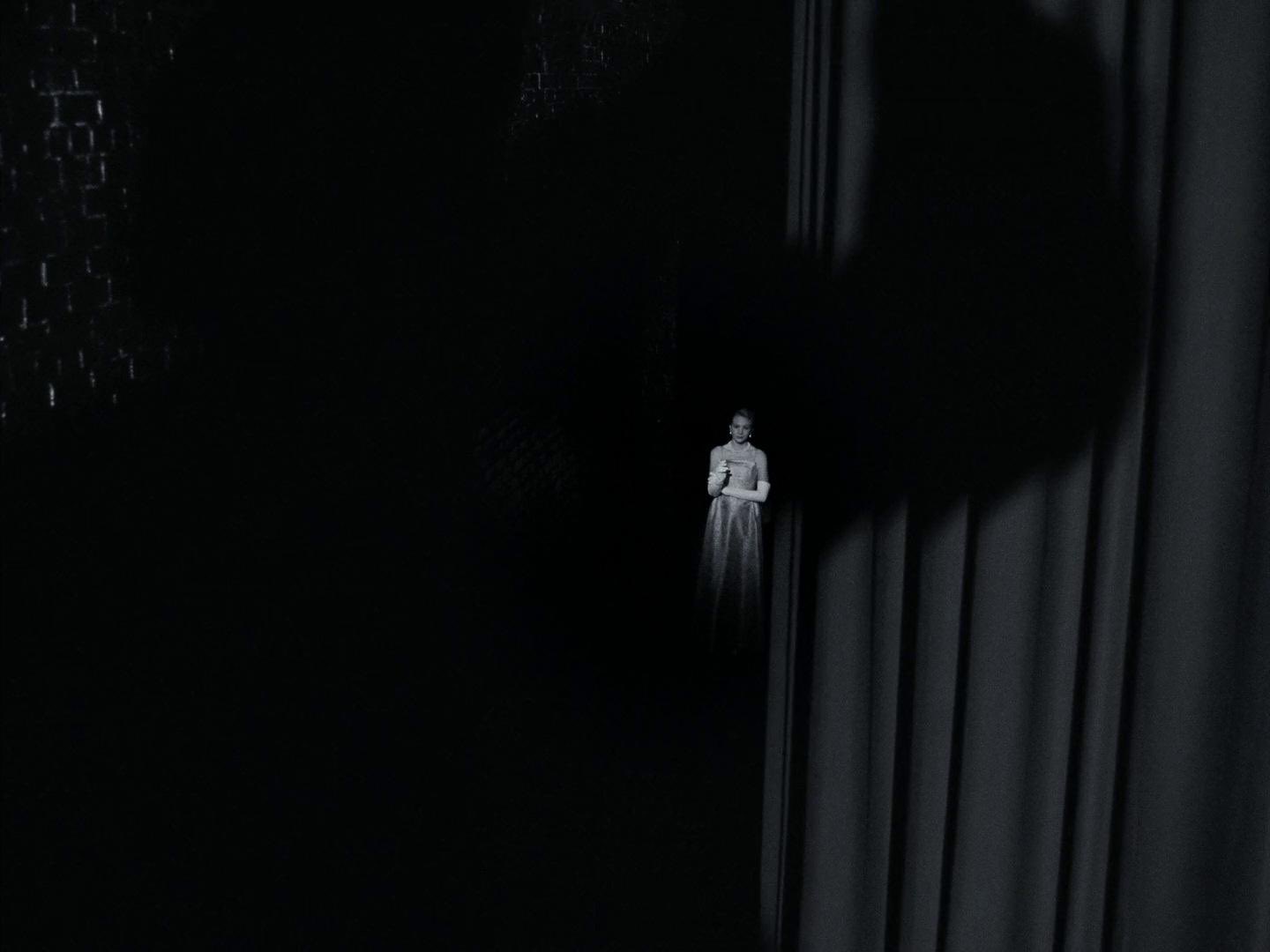

Beyond the controversy surrounding the film, are two gut-wrenching performances that standout as among the very best of the year. The relationship between Berstein and Montealegre is central to Berstein’s character arc and is used to note the passage of time within the film. When the two first meet, Leonard is experiencing his first major career success, while Felicia remains an understudy with big Broadway dreams. The two fall deeply in love, becoming each other’s creative muses, pushing each other towards greatness. However, Bernstein’s repressed sexuality begins to take a toll on their marriage and threatens his career as rumors spread about his relationships with other men. Mulligan takes great care to express Felicia’s disappointment, resentment, and hurt without judgment for who Bernstein is as an individual. She captures such an elegant longing for a life that’s just out of her reach, one where the man she loves, loves her and only her in return. The heartbreak she is able to portray with the subtlest of movements is a testament to her skill as an actor, but also Cooper’s directorial sense in letting the camera linger on her for almost an uncomfortable amount of time. The film demands that the audience takes Felicia’s hurt seriously, that we not only see it, we feel it. That emotional resonance is where Maestro shines as a film, it is unafraid to pull back the curtain and look backstage at the inner lives of the film’s leads.

Maestro’s score is almost entirely composed of the works of Leonard Berstein to great effect. The film assumes the audience has a baseline knowledge of Berstein’s work that the average modern moviegoer likely does not possess. This fault is exacerbated by the decision to have characters speak about Berstein’s greatness, while seldom showing him rise to the occasion. The opening scene where a young Berstein is offered a last minute opportunity to conduct the New York Philharmonic cuts out his performance as a conductor entirely, with Berstein explaining that he “blacked out” on stage. What I found lacking in the narrative, Cooper more than made up for by letting the music speak for itself and wash over the audience when necessary.

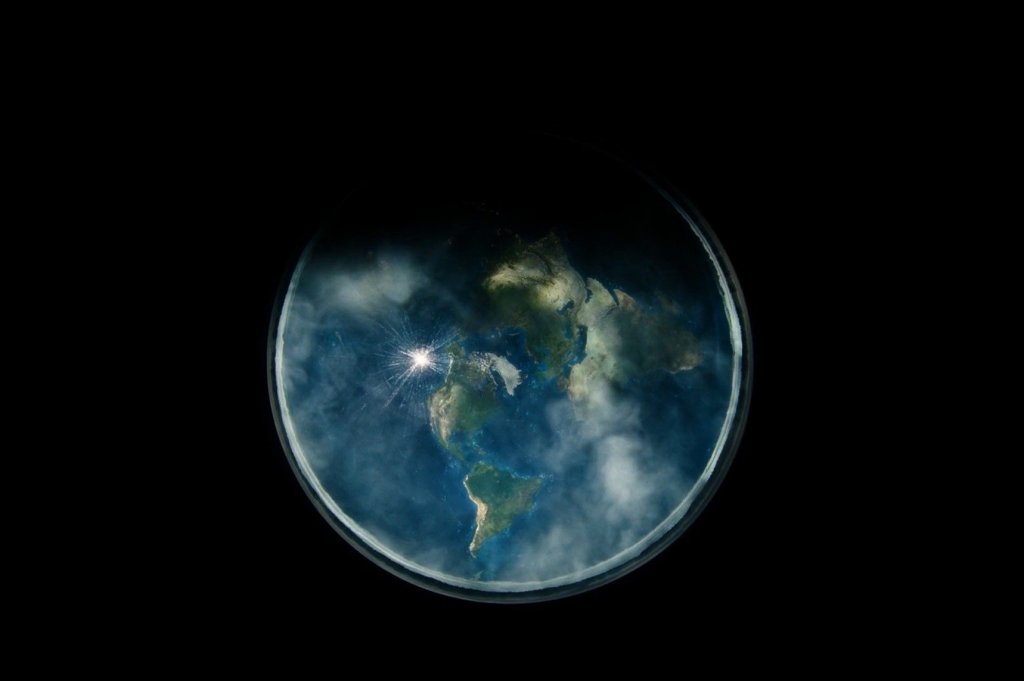

At about an hour and half into the film, we finally get to witness Bernstein’s conducting in action for a full five minutes. This scene allows the audience to experience the overwhelming joy and passion Bernstein had for classical works of music in a way that no line of dialogue could accurately replace. Perhaps this occurs too late in the film, as I was still left wanting to know who Leonard Bernstein the artist was before achieving his status as the greatest American conductor. Overall the musicality of Maestro is an essential part of the film’s storytelling, the flourishes and sweeping movements mark transitions between scenes and introduces new characters. The score gives the film, especially during the black and white portion, a more dreamlike quality in comparison to the family tragedy that unfolds in the color section. Each piece of music effectively elevates this film beyond what is simply seen on screen, transforming Maestro into the Golden Age movie musical it is so clearly inspired by.

What are you willing to sacrifice in the pursuit of greatness? This is the central question posed by Maestro. The film opens with a Bernstein quote, “A work of art does not answer questions, it provokes them; and its essential meaning is in the tension between the contradictory answers.” Felicia accepts a modest career as a television and stage actor, forgoing her dreams to be with the only man she’s ever truly loved, despite knowing it could never fully be reciprocated. She even admits to herself that it was her own arrogance to believe she could ever be satisfied by the relationship Leonard was able to provide. Yet she still misses him, there’s a heavy loneliness within her due to the sacrifices she’s made for her husband.

Conversely, Bernstein’s desire for artistic fulfillment is inhibited by the need to conceal his queer identity. This innate part of him presents roadblocks in his career and creates distance between himself and his family. Bernstein willingly sacrifices a piece of his personal happiness in order to achieve artistic greatness. However this distance also makes Maestro a bit of an alienating film to watch. Not because its themes are too far reaching or incoherent, but we’re left wondering who Bernstein really was as both a man and an artist by the time the credits roll. While I tend to agree with Bernstein that the purpose of art is not to answer life’s questions, a biopic should at least attempt to answer some of them. What’s left is a gorgeous and emotionally wrought film that’s lacking the substance to back up the passion so clearly displayed on screen.

Leave a comment