The Boy and the Heron is a thoughtful meditation on grief and legacy from Hayao Miyazaki, one of the greatest animated filmmakers of all time. It’s his first feature length film in ten years and by some accounts could be his last. Studio Ghibli denies those claims and stated earlier this year that Miyazaki continues to show up to the office, eager to plan his next film. Regardless, it is clear that the 82 year old is reflecting on his life through the story of The Boy and the Heron, one of his most autobiographical films to date. Miyazaki was born in Tokyo in 1941, the same year that Japan joined World War II. The film is set around 1944, opening with the fire bombing of Tokyo.

Mahito Maki, a twelve year old boy, is awoken to the sound of air raid sirens and his father leaving to rescue his mother, Hisako, who is working at the hospital downtown. Mahito follows after his father, rushing towards the towering inferno that has overtaken the hospital. The devastation reveals that Mahito’s mother was killed in the blaze. Miyazaki’s films have always dealt with mature themes, but this is by far the darkest and most intense opening scenes. Mahito’s desperation as he runs through the burning city is certainly the best animated sequence of this year, one that will stick with me for a long time. In the aftermath, Mahito and his father move out to a countryside estate owned by Natsuko, Hisako’s younger sister. The estate features a tower built by Mahito’s granduncle, a distinguished architect who vanished one day without a trace. Natsuko and Mahito’s father have since fallen in love and the two are expecting a child. Mahito resents Natsuko and has difficulty adjusting to his new life outside of the city, haunted by visions of the fire that took his mother’s life.

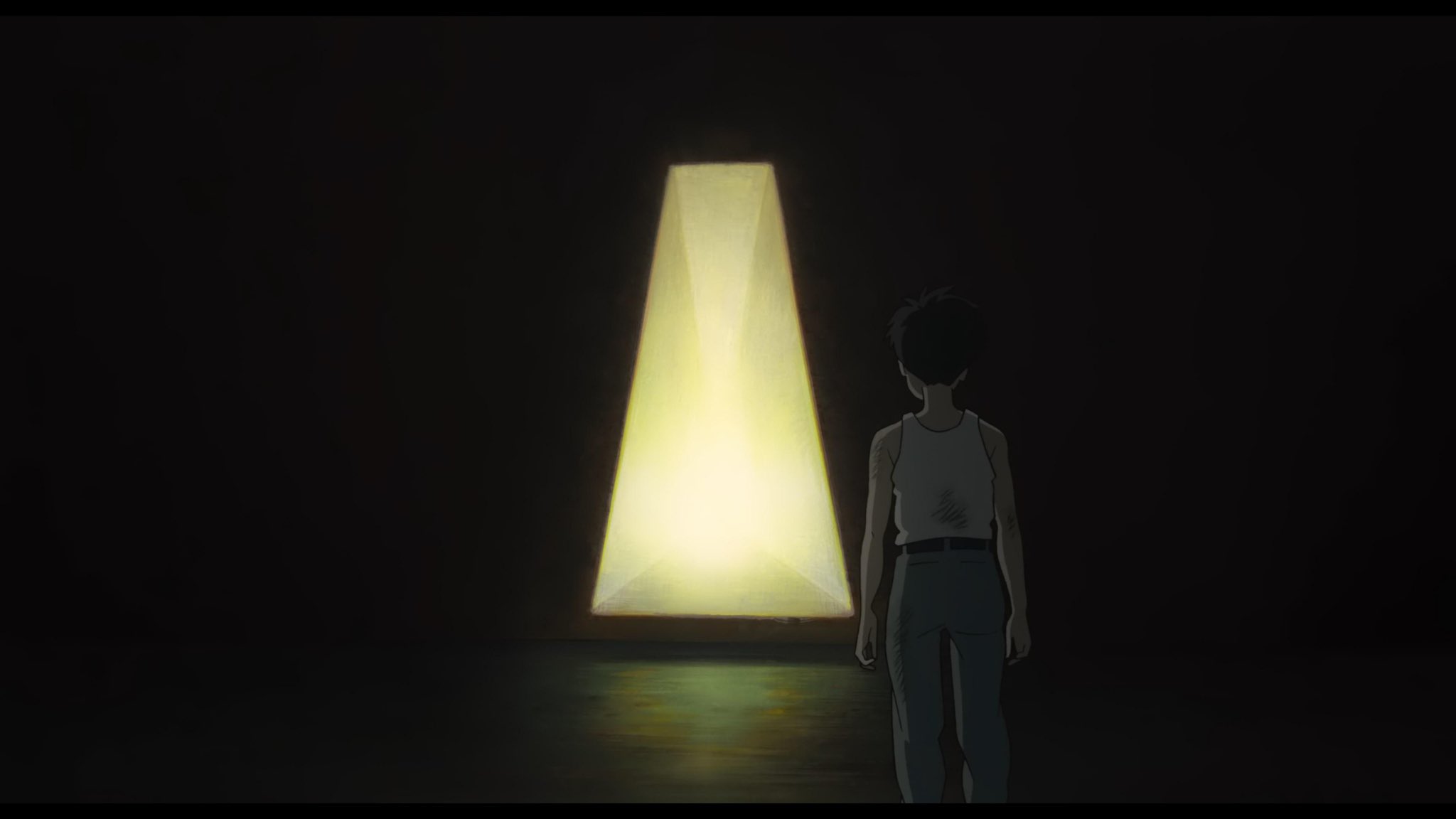

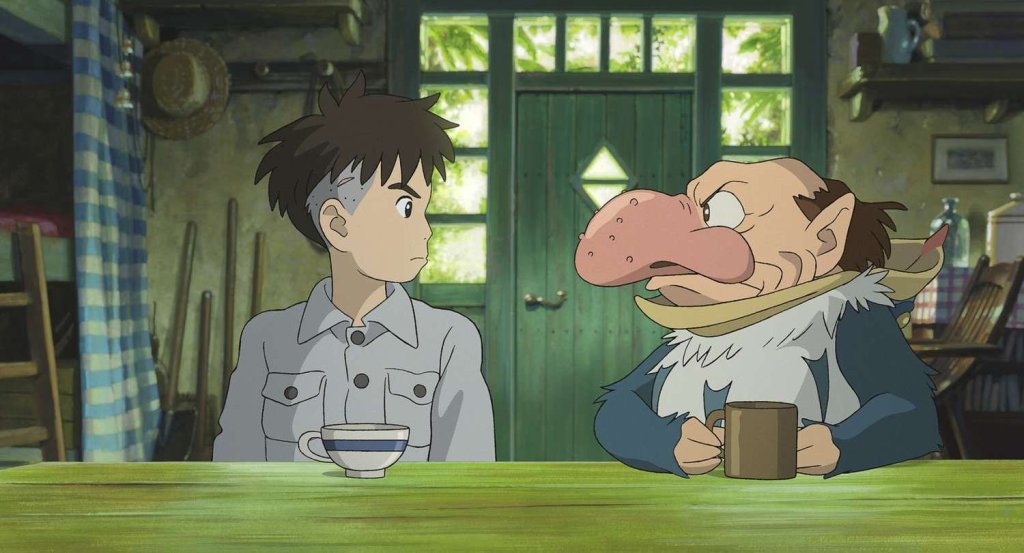

Everything changes when Natsuko wanders off in a trancelike state, disappearing into the tower. A mischievous grey heron taunts Mahito, claiming that his mother is still alive somewhere deep within the mysterious structure. The heron offers to guide Mahito towards her, rescuing Natsuko along the way. Despite their adversarial relationship, the two embark on a journey through a fantastical underworld full of otherworldly and outrageous creatures. This world is a beautifully crafted, heightened reality with endless possibilities and passages through time. The whole film is full of stunning, hand painted backdrops, but they really shine during this portion of The Boy and the Heron. With so many animated features today attempting to blend 2D style with 3D animation, it is such a breath of fresh air to see classic animation techniques so expertly done. If this is Miyazaki’s last film, it is truly a triumphant way to finish an already highly accomplished career.

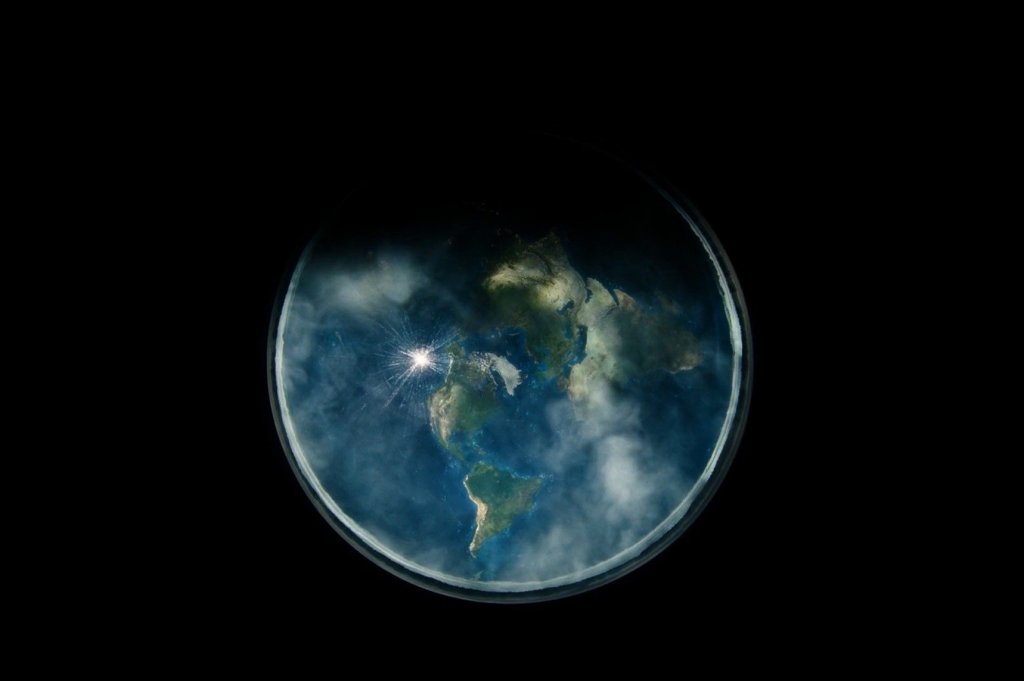

One of the creatures in this alternate world are the Warawara, an amorphous and adorable group of spirits who represent the souls yet to be born in Mahito’s world. Himi, a young woman who resembles Mahito’s own mother, uses her magical fire powers to defend the Warawara from a flock of hungry pelicans. The two form a connection which becomes essential in Mahito’s ability to process the grief of losing his own mother. The fire that killed her in his reality has now become a source of strength for Himi, recontextualizing Mahito’s pain. Himi agrees to assist Mahito in his rescue mission. Along the way, Mahito learns to accept Natsuko as his new mother, freeing her from her trance once and for all. The connection between the Warawara and Natsuko’s pregnancy speaks to Miyazaki’s concerns with leaving the world a better place for the next generation.

There’s an undercurrent of guilt about the chaotic state of the world that lingers throughout The Boy and the Heron. In the final scenes of the film, Mahito confronts his granduncle who is an all powerful wizard in this fantasy world. His granduncle begs Mahito to take over ruling the alternate dimension, citing how beautiful and perfect he could make it, improving upon it as his successor. However, Mahito refuses, choosing to instead return to his own, flawed reality and the fantasy world begins to crumble around them. Mahito and Natsuko manage to escape in time, returning to their life back home, now bonded as mother and son. Miyazaki depicts the world as a dangerous and unforgiving place beyond our control. The destruction of World War II and compounding issues facing our planet today, calls into question our ability to provide a safe, prosperous future for those who will inherit these problems. The Boy and the Heron warns us of the temptation to overindulge in escapism and isolation at a time when it has never been easier to witness all of the horrors of human suffering. Despite the pain and the difficulties that come with life, we must continue to work towards our collective future and do our best to leave the world a better place than it was when we first arrived.

Leave a comment